Resistance Training Following a Heart Attack

Early return to activity is important when recovering from a heart attack. It is important for patients to return to activity slowly and gradually progress the amount and intensity of exercise and activity over the first 4-6 weeks of leaving the hospital. With any activity or exercise, patients should continually monitor themselves for signs of exercise intolerance and adjust their activity or exercise accordingly. Patients are also instructed to stop the activity or exercise and notify a health care professional if they experience any cardiac symptoms.

In the hospital, the physiotherapist will review activity guidelines and recommend a home walking program. The time and frequency of walking is dependent on the individual’s previous level of activity. The goal is to gradually increase the duration of walking every week. A warm-up and cool down period should be incorporated before and after each walk, which includes walking at a slow pace or working at a lower intensity than the exercise portion of the walk. The physiotherapist will also discuss the process of returning to resistance training following a heart attack. The value and importance of resistance exercise is emphasized, however an initial hiatus from resistance training is recommended for the first few weeks of the acute heart healing period. This is due to the additional stress on the heart that strength training places, especially with repetitive use of the upper extremity.[1] During this period of time, return to aerobic exercise takes priority; once this period ends, it is time to begin initiating resistance training. This is where the cardiac rehabilitation (CR) program comes in.

Patients recovering from a heart attack are referred to cardiac rehabilitation and are highly encouraged to participate, ideally within 4 weeks of hospital discharge. In CR, a health care provider will review factors such as severity of heart damage, resting ejection fraction, symptoms and previous level of activity to determine risk stratification prior to providing an exercise prescription.

First, aerobic exercise is progressed in a supervised environment, working towards a goal of 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week. In most cases, resistance exercise can be introduced after performing aerobic exercise in CR for 2-4 weeks without cardiac symptoms.[2] It is recommended that an exercise professional supervise resistance training initially to ensure proper technique. Low-level resistance training exercises using resistance bands, resistance tubing or light dumbbells are typically performed first and progressed to heavier exercises involving dumbbells, barbells, kettlebells and/or weight machines as the patient is safe and able. The exercises selected are those that incorporate major muscle groups and multi-joint movements that can be performed safely.

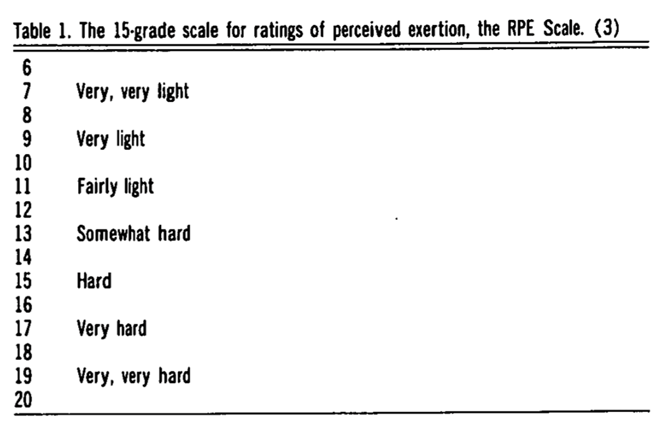

The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale is often used to guide exercise intensity (see chart below). Generally, the weight chosen for an exercise should allow a patient to be working at a moderate intensity (RPE 11-13) for 1-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions.

Borg GA (1982). Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 14 (5): 377-381. doi:10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012.

The resistance training program should be progressed to ultimately include 8-10 exercises performed 2-3 times per week on non-consecutive days.[3] Concentric-eccentric movements are encouraged over isometric movements, and patients are encouraged to move loads slowly using correct technique with emphasis on avoiding holding their breath (Valsalva maneuver).[4]

Progression is based on the patient’s perception of “moderate fatigue” after performing the exercise. Once a patient has rated an exercise at an RPE level less than 11 after performing 3 sets of 15 repetitions, it is recommended to increase the weight approximately 5% per week and decrease to 3 sets of 10 repetitions.

Keep in mind that recovery timelines can vary for individuals and resistance training may not be recommended in all cases.

Submitted by:

Lisa Gibson (Physiotherapist at Wellness Institute)

Allison Hay (Physiotherapist at St. Boniface Hospital)

Jayms Kornelsen (Kinesiologist at Wellness Institute)

Becca Krahn (Physiotherapist at St. Boniface Hospital)

References:

[1] Kang J, Chaloupka EC, Mastrangelo MA, Angelucci J. Physiological responses to upper body exercise on an arm and a modified leg ergometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(10):1453-1459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199910000-00015

[2] Tocco, A., Matz, K., Huls, S., Zavala, M., Sexton, J. Human Kinetics. (2013). Modifiable Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. In Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs (pp. 114–121). essay.

[3] Kirkman, D. L., Lee, D., & Carbone, S. (2022). Resistance exercise for cardiac rehabilitation. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 70, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2022.01.004

[4] Pollock, M.L., Franklin, B.A, Balady, G.J., Chaitman, B.L., Fleg, J.L., Fletcher, B., Limacher, M., Pina, I.L, Stein, R.A, Williams, M., & Bazzarre, T. (2000). Resistance Exercise in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease. Benefits, Rationale, Safety And Prescription An Advisory From The Committee On Exercise, Rehabilitation, And Prevention, Council On Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association, 101, 828-833. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.7.828